Why Is Caligraphy the Highest Form of Islamic Art

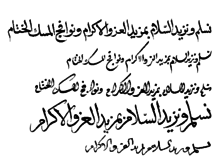

The Basmala in an 18th-century Islamic calligraphy from the Ottoman region, Thuluth script

Islamic calligraphy is the artistic exercise of handwriting and calligraphy, in the languages which utilise Standard arabic alphabet or the alphabets derived from it. Information technology includes Standard arabic, Persian, Ottoman, and Urdu calligraphy.[one] [2] It is known in Standard arabic every bit khatt Arabi ( خط عربي ), which translates into Arabic line, pattern, or structure.[3]

The development of Islamic calligraphy is strongly tied to the Qur'an; chapters and excerpts from the Qur'an are a common and almost universal text upon which Islamic calligraphy is based. Although creative depictions of people and animals are not explicitly forbidden past the Qur'an, pictures take traditionally been express in Islamic books in order to avoid idolatry. Although some scholars dispute this, Kufic script was supposedly developed around the end of the 7th century in Kufa, Iraq, from which it takes its name. The manner later adult into several varieties, including floral, foliated, plaited or interlaced, bordered, and square kufic. In the aboriginal world, though, artists would often get around this prohibition by using strands of tiny writing to construct lines and images. Calligraphy was a valued art form, even every bit a moral good. An ancient Standard arabic proverb illustrates this point past emphatically stating that "Purity of writing is purity of the soul."[4]

Notwithstanding, Islamic calligraphy is not limited to strictly religious subjects, objects, or spaces. Similar all Islamic art, it encompasses a diverse array of works created in a wide variety of contexts.[five] The prevalence of calligraphy in Islamic fine art is not directly related to its non-figural tradition; rather, it reflects the centrality of the notion of writing and written text in Islam.[six] For instance, the Islamic prophet Muhammad is related to have said: "The start thing God created was the pen."[7]

Islamic calligraphy developed from two major styles: Kufic and Naskh. In that location are several variations of each, as well every bit regionally specific styles. Standard arabic or Farsi calligraphy has as well been incorporated into modern fine art, beginning with the mail service-colonial menstruum in the Centre East, as well every bit the more recent style of calligraffiti.

Instruments and media [edit]

The traditional instrument of the Islamic calligrapher is the kalam, a pen normally made of dried reed or bamboo. The ink is often in colour and chosen so that its intensity tin vary profoundly, creating dynamism and movement in the letter of the alphabet forms. Some styles are often written using a metallic-tip pen.

Five chief Standard arabic calligraphic cursive styles:

- Naskh

- Nasta'liq

- Diwani

- Thuluth

- Reqa

Islamic calligraphy tin can be practical to a broad range of decorative mediums other than paper, such as tiles, vessels, carpets, and rock.[ii] Before the advent of paper, papyrus and parchment were used for writing. During the 9th century, an influx of paper from Communist china revolutionized calligraphy. While monasteries in Europe treasured a few dozen volumes, libraries in the Muslim world regularly contained hundreds and fifty-fifty thousands of books.[i] : 218

For centuries, the art of writing has fulfilled a cardinal iconographic role in Islamic art.[viii] Although the academic tradition of Islamic calligraphy began in Baghdad, the heart of the Islamic empire during much of its early on history, information technology somewhen spread equally far as India and Spain.

Coins were another support for calligraphy. Beginning in 692, the Islamic caliphate reformed the coinage of the Near Eastward past replacing Byzantine Christian imagery with Islamic phrases inscribed in Arabic. This was specially true for dinars, or gold coins of high value. Mostly, the coins were inscribed with quotes from the Qur'an.

By the tenth century, the Persians, who had converted to Islam, began weaving inscriptions onto elaborately patterned silks. So precious were textiles featuring Arabic text that Crusaders brought them to Europe equally prized possessions. A notable example is the Suaire de Saint-Josse, used to wrap the bones of St. Josse in the Abbey of St. Josse-sur-Mer, virtually Caen in north-western France.[i] : 223–5

As Islamic calligraphy is highly venerated, well-nigh works follow examples set by well-established calligraphers, with the exception of secular or gimmicky works. In the Islamic tradition, calligraphers underwent extensive training in three stages, including the study of their teacher's models, in order to exist granted certification.[vii]

Styles [edit]

Kufic [edit]

Kufic is the oldest form of the Standard arabic script. The style emphasizes rigid and angular strokes, which appears as a modified grade of the old Nabataean script.[9] The Primitive Kufi consisted of near 17 letters without diacritic dots or accents. Diacritical markings were added during the 7th century to assist readers with pronunciation of the Qur'an and other important documents, increasing the number of Standard arabic letters to 28.[10] Although some scholars dispute this, Kufic script was supposedly developed around the terminate of the 7th century in Kufa, Republic of iraq, from which it takes its proper noun.[eleven] The way after adult into several varieties, including floral, foliated, plaited or interlaced, bordered, and square kufic. Due to its straight and orderly style of lettering, Kufic was ofttimes used in ornamental rock carving likewise as on coins.[12] It was the principal script used to re-create the Qur'an from the 8th to tenth century and went out of general utilize in the twelfth century when the flowing naskh style become more practical. Still, it continued to exist used as a decorative element to dissimilarity superseding styles.[13]

There was no set up rules of using the Kufic script; the simply common feature is the angular, linear shapes of the characters. Due to the lack of standardization of early on Kufic, the script differs widely betwixt regions, ranging from very foursquare and rigid forms to flowery and decorative ones.[14]

Common varieties include[xiv] square Kufic, a technique known every bit banna'i.[15] Contemporary calligraphy using this style is also popular in modernistic decorations.

Decorative Kufic inscriptions are often imitated into pseudo-kufics in Middle age and Renaissance Europe. Pseudo-kufics is especially mutual in Renaissance depictions of people from the Holy Land. The exact reason for the incorporation of pseudo-Kufic is unclear. Information technology seems that Westerners mistakenly associated 13th-14th century Middle Eastern scripts with systems of writing used during the time of Jesus, and thus institute it natural to represent early Christians in association with them.[16]

Naskh and Thuluth [edit]

Naskh [edit]

The employ of cursive scripts coexisted with Kufic, and historically cursive was commonly used for informal purposes.[17] With the rise of Islam, a new script was needed to fit the pace of conversions, and a well-defined cursive chosen naskh start appeared in the 10th century. Naskh translates to "copying," as it became the standard for transcribing books and manuscripts.[eighteen] The script is the nearly ubiquitous among other styles, used in the Qur'an, official decrees, and individual correspondence.[19] Information technology became the basis of modern Standard arabic print.

Standardization of the style was pioneered by Ibn Muqla (886 – 940 A.D.) and subsequently expanded by Abu Hayan at-Tawhidi (died 1009 A.D.). Ibn Muqla is highly regarded in Muslim sources on calligraphy equally the inventor of the naskh style, although this seems to exist erroneous. Since Ibn Muqla wrote with a distinctly rounded mitt, many scholars drew the decision that he founded this script. Ibn al-Bawwab, the student of Ibn Muqla, is actually believed to accept created this script.[xviii] However, Ibn Muqla did institute systematic rules and proportions for shaping the messages, which utilise 'alif every bit the x-height, and the dot as basic measurement.[20]

Thuluth [edit]

Thuluth was developed during the 10th century and slowly refined by Ottoman Calligraphers including Mustafa Râkim, Shaykh Hamdallah, and others, till it became what it is today. Letters in this script take long vertical lines with broad spacing. The proper name, significant "i third", may possibly be a reference to the 10-height, which is one-third of the 'alif, or to the fact that the pen used to write the vowels and ornaments is ane third the width of that used in writing the letters.[21]

Variations:

- Reqa' is a handwriting style similar to thuluth. Information technology commencement appeared in the 10th century. The shape is simple with short strokes and minor flourishes. Yaqut al-Musta'simi was i of the calligraphers who employed this style.[22] [23]

- Muhaqqaq is a imperial style used by accomplished calligraphers, and is a variation of thuluth. Forth with thuluth, it was considered one of the nigh beautiful scripts, as well as one of the nigh hard to execute. Muhaqqaq was commonly used during the Mamluk era, but its use became largely restricted to short phrases, such as the basmallah, from the 18th century onward.[24]

Regional styles [edit]

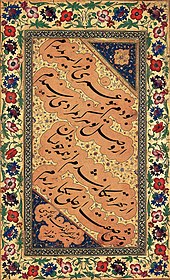

Nasta'liq calligraphy of a Persian poem by Mir Emad Hassani, maybe the about celebrated Persian calligrapher

With the spread of Islam, the Arabic script was established in a vast geographic surface area with many regions developing their own unique style. From the 14th century onward, other cursive styles began to develop in Turkey, Persia, and China.[19]

- Maghrebi scripts developed from Kufic letters in the Maghreb (N Africa) and al-Andalus (Iberia), Maghrebi scripts are traditionally written with a pointed tip (القلم المذبب), producing a line of even thickness. Within the Maghrebi family, there are different styles including the cursive mujawher and the formalism mabsut.

- Sudani scripts adult in Biled every bit-Sudan (the Westward African Sahel) and can be considered a subcategory of Maghrebi scripts

- Diwani is a cursive style of Standard arabic calligraphy adult during the reign of the early Ottoman Turks in the 16th and early 17th centuries. It was invented by Housam Roumi, and reached its elevation of popularity under Süleyman I the Magnificent (1520–1566).[25] Spaces between messages are often narrow, and lines ascend upward from right to left. Larger variations chosen djali are filled with dense decorations of dots and diacritical marks in the space between, giving it a compact appearance. Diwani is hard to read and write due to its heavy stylization and became the ideal script for writing court documents as it ensured confidentiality and prevented forgery.[xiv]

- Nasta'liq is a cursive style originally devised to write the Farsi language for literary and non-Qur'anic works.[14] Nasta'liq is thought to be a afterwards development of the naskh and the earlier ta'liq script used in Islamic republic of iran.[26] Quite rapidly gaining popularity equally a script in South Asia. The name ta'liq means "hanging," and refers to the slightly sloped quality of lines of text in this script. Letters take short vertical strokes with broad and sweeping horizontal strokes. The shapes are deep, hook-like, and have high dissimilarity.[14] A variant chosen Shikasteh was adult in the 17th century for more formal contexts.

- Sini is a style adult in China. The shape is profoundly influenced past Chinese calligraphy, using a horsehair castor instead of the standard reed pen. A famous modern calligrapher in this tradition is Hajji Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang. [27]

Modern [edit]

In the post-colonial era, artists working in North Africa and the Center East transformed Arabic calligraphy into a modern art move, known every bit the Hurufiyya movement.[28] Artists working in this style use calligraphy every bit a graphic element inside contemporary artwork.[29] [thirty]

The term, hurufiyya is derived from the Standard arabic term, harf for letter. Traditionally, the term was charged with Sufi intellectual and esoteric meaning.[28] Information technology is an explicit reference to a medieval arrangement of teaching involving political theology and lettrism. In this theology, messages were seen every bit primordial signifiers and manipulators of the cosmos. [31]

Hurufiyya artists blended Western art concepts with an creative identity and sensibility drawn from their own culture and heritage. These artists integrated Islamic visual traditions, specially calligraphy, and elements of mod art into syncretic gimmicky compositions.[32] Although hurufiyyah artists struggled to find their own individual dialogue within the context of nationalism, they also worked towards an aesthetic that transcended national boundaries and represented a broader amalgamation with an Islamic identity.[28]

The hurufiyya artistic way every bit a movement most likely began in North Africa around 1955 with the piece of work of Ibrahim el-Salahi.[28] However, the apply of calligraphy in modern artworks appears to take emerged independently in various Islamic states. Artists working in this were oft unaware of other hurufiyya artists's works, allowing for different manifestations of the style to sally in different regions.[33] In Sudan, for instance, artworks include both Islamic calligraphy and West African motifs.[34]

The Roof of Frere Hall, Karachi, Pakistan, c. 1986. Landscape by artist, Sadequain Naqqash integrates calligraphy elements into a mod artwork.

The hurufiyya art move was not confined to painters and included artists working in a multifariousness of media.[35] One example is the Jordanian ceramicist, Mahmoud Taha who combined the traditional aesthetics of calligraphy with skilled craftsmanship.[36] Although not affiliated with the hurufiyya movement, the contemporary artist Shirin Neshat integrates Arabic text into her black-and-white photography, creating contrast and duality. In Republic of iraq, the movement was known every bit Al Bu'd al Wahad (or the Ane Dimension Group)",[37] and in Iran, it was known as the Saqqa-Khaneh move.[28]

Western art has influenced Arabic calligraphy in other ways, with forms such as calligraffiti, which is the use of calligraphy in public art to make politico-social messages or to ornamentation public buildings and spaces.[38] Notable Islamic calligraffiti artists include: Yazan Halwani active in Lebanese republic [39] , el Seed working in France and Tunisia, and Caiand A1one in Tehran.[twoscore]

In 2017 the Sultanate of Oman unveiled the Mushaf Muscat, an interactive calligraphic Quran following supervision and back up from the Omani Ministry building of Endowments and Religious Diplomacy, a voting fellow member of the Unicode Consortium.[41]

Gallery [edit]

Kufic [edit]

-

Kufic script in an 11th-century Qur'an

-

Square kufic tilework in Yazd, Islamic republic of iran

-

Nether-coat terra cotta bowl from the 11th century Nishapur

Naskh and Thuluth [edit]

-

Muhaqqaq script in a 15th-century Qur'an from Turkey

-

Muhaqqaq script in a 13th-century Qur'an

-

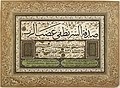

Naskh script in an early on 16th-century Ottoman manuscript dedicated to Selim I

-

Diploma of competency in calligraphy, written with thuluth and naskh script

Regional varieties [edit]

Modern examples [edit]

Craft [edit]

-

The instruments and work of a pupil calligrapher

-

Islamic calligraphy performed by a Malay Muslim in Malaysia. Calligrapher is making a crude typhoon.

Listing of calligraphers [edit]

Some classical calligraphers:

- Medieval

- Ibn Muqla (d. 939/940)

- Ibn al-Bawwab (d. 1022)

- Fakhr-united nations-Nisa (12th century)

- Yaqut al-Musta'simi (d. 1298)

- Mir Ali Tabrizi (d. 14th–15th century)

- Ottoman era

- Shaykh Hamdullah (1436–1520)

- Hamid Aytaç (1891-1982)

- Seyyid Kasim Gubari (d. 1624)

- Hâfiz Osman (1642–1698)

- Mustafa Râkim (1757–1826)

- Mehmed Shevki Efendi (1829–1887)

- Contemporary

- Abdul Djalil Pirous, known as A.D. Pirous (b. 1933), Indonesian painter and lecturer

- Ali Adjalli (b. 1939), Iranian primary calligrapher, painter, poet and educator

- Wijdan Ali (b. 1939), Jordan

- Hashem Muhammad al-Baghdadi (1917-1973), Iraq

- Mohammad Hosni (1894-1964), Syria

- Shakkir Hassan Al Sa'id (1925-2004), Iraq

- Madiha Omar (1908-2005), Iraqi-American

- Sadequain Naqqash (1930-1987), Pakistan

- Ibrahim el-Salahi (b. 1930), Sudan

- Mahmoud Taha (b. 1942), Jordan

- Charles Hossein Zenderoudi (b. 1937), Iran

- Abdulraouf Baydoun (b. 1956), Syria

- Mohamed Zakariya (b. 1942), United states of america

- Hassan Massoudy (b. 1944), Iraq, France

- Amir Kamal (b. 1972), Pakistan

- Uthman Taha (b. 1934), Syria

- Abas Baghdadi, Iraq

- Mothanna Al-Obaydi, Iraq

See likewise [edit]

- Illuminated manuscript

- Islamic compages

- Islamic Gilded Historic period

- Islamic graffiti

- Islamic miniature

- Islamic pottery

- Museum of Turkish Calligraphy Art

- Ottoman Turkish language

- Farsi calligraphy

- Sini (script)

- Uthman Taha

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Blair, Sheila S.; Bloom, Jonathan One thousand. (1995). The art and architecture of Islam : 1250–1800 (Reprinted with corrections ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN0-300-06465-9.

- ^ a b Chapman, Caroline (2012). Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Compages, ISBN 978-979-099-631-1

- ^ Julia Kaestle (ten July 2010). "Arabic calligraphy equally a typographic exercise".

- ^ Lyons, Martyn. (2011). Books : a living history. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN978-i-60606-083-four. OCLC 707023033.

- ^ Blair, Sheila S. (Spring 2003). "The Mirage of Islamic Art: Reflections on the Study of an Unwieldy Field". The Art Bulletin. 85: 152–184 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Allen, Terry (1988). 5 Essays on Islamic Art. Sebastopol, CA: Solipsist Press. pp. 17–37. ISBN 0944940005.

- ^ a b Roxburgh, David J. (2008). ""The Eye is Favored for Seeing the Writing'south Course": On the Sensual and the Sensuous in Islamic Calligraphy". Muqarnas. 25: 275–298 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Tabbaa, Yasser (1991). "The Transformation of Arabic Writing: Part I, Qur'ānic Calligraphy". Ars Orientalis. 21: 119–148.

- ^ Flood, Necipoğlu (2017). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. I. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 109–110. ISBN9781119068570. OCLC 963439648.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (1984). Calligraphy and Islamic Culture. New York: New York University Press. p. four. ISBN 0814778305.

- ^ Kvernen, Elizabeth (2009). "An Introduction of Arabic, Ottoman, and Persian Calligraphy: Style". Calligraphy Qalam., Schimmel, Annemarie (1984). Calligraphy and Islamic Culture. New York: New York University Press. p. iii. ISBN 0814778305.

- ^ Ul Wahab, Zain; Yasmin Khan, Romana (xxx June 2016). "The Element of Mural Art and Mediums in Potohar Region". Journal of the Research Guild of Pakistan. Vol. 53; No. one – via Nexis Uni.

- ^ "Kūfic script". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b c d east Kvernen, Elizabeth (2009). "An Introduction of Standard arabic, Ottoman, and Persian Calligraphy: Mode". Calligraphy Qalam.

- ^ Jonathan 1000. Blossom; Sheila Blair (2009). The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture. Oxford University Press. pp. 101, 131, 246. ISBN978-0-xix-530991-i . Retrieved iv January 2012.

- ^ Mack, Rosamond East. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600, University of California Printing, 2001 ISBN 0-520-22131-1

- ^ Mamoun Sakkal (1993). "The Art of Arabic Calligraphy, a brief history".

- ^ a b Blair, Sheila S. (2006). Islamic Calligraphy. Edinburgh Academy Press. pp. 158, 165. ISBN 0748612122.

- ^ a b "Library of Congress, Selections of Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Calligraphy: Qur'anic Fragments". International.loc.gov. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Kampman, Frerik (2011). Arabic Typography; its past and its future

- ^ Kvernen, Elisabeth (2009). "Thuluth and Naskh". CalligraphyQalam . Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "خط الرقاع". instance.ampproject.org . Retrieved 16 April 2021.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Kvernen, Elizabeth (2009). "Tawqi' and Riqa'". CalligraphyQalam . Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Mansour, Nassar (2011). Sacred Script: Muhaqqaq in Islamic Calligraphy. New York: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84885-439-0

- ^ "Diwani script". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Ta'liq Script". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Gallery" Archived 31 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Haji Noor Deen.

- ^ a b c d e Flood, Necipoğlu (2017). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume II. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1294. ISBN 1119068665. OCLC 1006377297.

- ^ Mavrakis, North., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Eye Eastern Art", McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Weblog

- ^ A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56

- ^ Mir-Kasimov, O., Words of Ability: Hurufi Teachings Between Shi'ism and Sufism in Medieval Islam, I.B. Tauris and the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2015

- ^ Lindgren, A. and Ross, S., The Modernist World, Routledge, 2015, p. 495; Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Motility in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online: https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-five/; Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette Great britain, 2015, p. 56

- ^ Dadi. I., "Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective," South Atlantic Quarterly, 109 (3), 2010, pp. 555–576, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-2010-006; Overflowing, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Fine art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ^ Overflowing, Necipoğlu (2017). A Companion to Islamic Fine art and Compages. Volume II. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1298-1299. ISBN 1119068665. OCLC 1006377297.

- ^ Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Fine art Motion in Center Eastern Art," McGill Periodical of Middle Eastern Studies Web log, Online: https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-5/;Tuohy "Unknown". Retrieved 25 March 2020. [ dead link ] , A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56; Dadi. I., "Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective," South Atlantic Quarterly, 109 (3), 2010, pp. 555–576, DOI:https://doi.org/ten.1215/00382876-2010-006

- ^ Asfour. M., "A Window on Contemporary Arab Fine art," NABAD Art Gallery, Online: http://world wide web.nabadartgallery.com/

- ^ "Shaker Hassan Al Said," Darat al Funum, Online: www.daratalfunun.org/primary/activit/curentl/anniv/exhib3.html; Overflowing, Necipoğlu (2017). A Companion to Islamic Fine art and Architecture. Volume II. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1294. ISBN 1119068665. OCLC 1006377297.

- ^ Grebenstein, M., Calligraphy Bible: A Complete Guide to More 100 Essential Projects and Techniques, 2012, p. 5

- ^ Alabaster, Olivia. "I like to write Beirut as it's the metropolis that gave us everything", The Daily Star, Beirut, 9 February 2013

- ^ Vandalog (iii May 2011). "A1one in Tehran Iran". Vandalog . Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ Martin Lejeune, 15 June 2017, Oman unveils earth'southward 1st interactive calligraphic Quran

External links [edit]

- Islamic Calligraphy Pictures

- Mushaf Muscat

- mastersofistanbul.com

- baradariarts.com

- Gallery with much calligraphy in Turkish mosque

- Anthology of Persian calligraphers from 10th to 20th centuries

griffinwhisingerrim91.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_calligraphy

Post a Comment for "Why Is Caligraphy the Highest Form of Islamic Art"